For all the travelling I’ve done, it’s always good to come home. I am writing these words 50m away from the River Slaney, in the south east of Ireland, with a a copy of Crossabeg: The Parish and its People (Vol 2) waiting for me. And I’m honoured to be featured in the book. When my neighbour here, Alice Devine, one of the team who put the book together asked me to write something about my travels, I thought the best way was to show how my upbringing in Crossabeg provided the foundation for everything that followed – including my trips to the Arctic and the Antarctic. For those of you not able to get your hands on the book, here’s what I wrote:

September 2003: I was trussed up in a wetsuit, sitting in an inflatable boat off the coast of Corfu, in Greece, at the tail end of a scuba diving course. I’d just surfaced from a great dive with a friend, and as the hull of the boat beat against the Adriatic on the way back to shore, I had moment of clarity.

I’m sitting in a boat, on the sea, and it feels normal.

Why does it feel normal?

Because I grew up messing around on boats on the River Slaney.

So why am I wasting my time sitting in a basement office in Dublin, staring at a screen, when I could be doing something else?

I quickly did a sum up of what I wanted, and what resources I had.

Something outdoors. Ships, boats, oceans, wildlife. Hopefully something that could benefit the planet’s environment, a role where I can use my head.

What do I do? I write. Web stuff. Some photography.

Who might give me a job?

Well, Greenpeace have ships, and campaign for the environment. Maybe I could work for them.

Back in Ireland, I foraged the Internet for information, jobs. Fired a CV to Greenpeace, no reply for a while. I talked to the right people about logistics jobs in Antarctica, mountain guiding in the Himalayas. No option was overlooked, as I maintained enthusiasm through the autumn. I went into self-improvement overdrive. I did a first aid course, and a Powerboat certificate in a gale off Malahide. Did my next Scuba certificate off Killary Harbour in November, also at the end of some shocking weather. When an adventure came my way, I was ready.

As Christmas approached, Greenpeace advertised for a web editor its Amsterdam HQ. Ok, I thought, it’s another desk job, but it’s a foot in the door. I got an interview, head to Amsterdam, where, I put both feet inside the door.

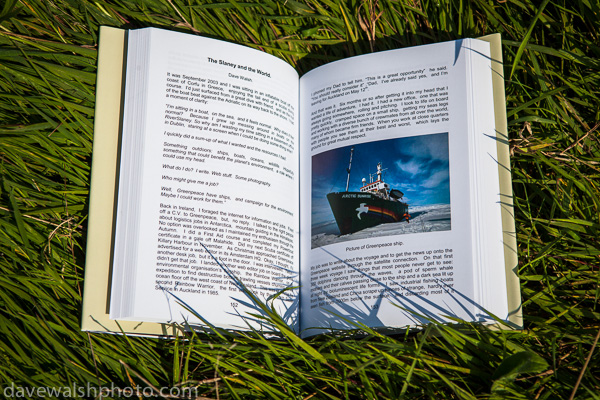

But I didn’t get that job. I landed another one – on board the global environmental organisation’s flagship, the second Rainbow Warrior. The ship of that name was sunk by the French Secret Service mine in Auckland in 1985, before it sailed to protest against nuclear tests in the Pacific. I joined second warrior in May 2004, just a few hundred metres away from where the 1985 attack happened, to take part in an expedition would search for bottom trawling vessels off the coast of New Zealand. Bottom trawling is an appalling destructive fishing practice that involves dragging a massive weighted net along the ocean floor at depths of a 1000m – destroying everything in its path. It’s been compared a hunter destroying a forest just to catch a few birds or rabbits. Back in 2004, this form of ecocide this was out of sight, out of mind, but thanks to our publicizing of the issue – through photography and video, it’s become globally condemned practice, despite a failed UN attempt to ban it.

I phoned my dad, to tell him about the job.

“This is a great opportunity”, he said. “You should really consider it”.

“Dad, I’ve already said yes, and I’m leaving for Auckland on May 12th”

And that was it. Six months after getting it into my head that I desired a life of adventure, I had it. I had a new office, one that was always going somewhere, rolling and pitching in the waves. I took to life on board pretty quickly, getting used to the cramped space on a small ship, getting my sea legs, and working with a diverse bunch of crewmates from all over the world, many of whom became firm friends. When you work at close quarters with people, you see them at the best and worst, which lays the ground for great mutual respect – you look out for each other.

My job was to write about the voyage, and to get the news up onto the Greenpeace website, through the satellite connection. On that first three week voyage, I saw things that most people never get to see; 300 dolphins dancing through the waves, a pod of sperm whale mothers and their calves passing close to the ship and a dark sea lit up at night by bioluminescent lifeforms. I saw industrial bottom trawling boats from New Zealand and China scrape up tonnes of strange, hardly ever seen fish and rare corals from 1000m below the surface, and discarding most of it overboard. We wired the images to colleagues at the UN in New York, where a Law of the Sea Meeting was taking place, exposing the destructive, wasteful fishing that was going on out of sight, out of mind.

By October I was back on a Greenpeace ship again, an ex-Soviet era firefighting ship, refitted, re-purposed and renamed the Esperanza. I joined in Falmouth, Cornwall, and we headed from there up Ireland’s west coast to Killybegs, and out into the Atlantic weather, looking once again for bottom trawlers, with Captain John Castle in command. During this voyage, I took an oath – to never, ever complain about weather on land again. It’s only when you’ve been on a 72m long box of steel, being bounced around incessantly for a couple of weeks in force 10 gales, you come to realise that a bit of drizzle is nothing to moan about.

But despite the toughness of the conditions, the expedition had its highlights – seeing the night sky glow red under the Aurora Borealis; Sailing through the islands of St Kilda, off the Hebrides, fog wreathing the sea stacks, and dolphins acting as pilots either side of us. And best of all, sailing up the Liffey on a foggy Halloween Sunday morning, before taking my family and friends on a tour of the ship and organisation that had become part of me, and I of it.

It was around then that people started asking me – how did you get into all this? I started thinking about it. The ship stuff I could understand – I’d grown up in a house filled with books of maps and ships, thanks to my Dad. The Slaney might be a river, but as it hooks around the west side of Crossabeg, it’s salty, and tidal. One of the regular questions in our house is “What’s the tide doing?” My brother Mick also took the seas, as a ship’s engineer, and has sailed the world’s oceans as much as I have.

Before Greenpeace, I had flirted with various environmental issues, but would never thought of myself as an environmental campaigner. Yet, growing up in Ballydicken, I now realise that an appreciation of the natural environment was inherent. We – my sister, Suzanne and I, and later, Mick had the run of the country, and knew every tree and stream that would in our imaginations, become part of a vast jungle. My dog Oscar and I were always running in to foxes and hares when out wandering, or out exploring the Slaney in our boat.

As a 12-yr old, I spent my summer days either out in boat (built by next door neighbour Jim Devine) with my dog Oscar or gone fishing for the bass that would come up to Killurin Bridge during the summer. There was plenty of black estuary mud outside our house (I fell in it often enough), where my dad told me it was sand and gravel during his childhood. I never thought too much of this, or of the green rafts of vegetation that would choke the river during the hottest days of the year. I realise now that the river was being slowly suffocated by excess nutrients, from agricultural fertiliser, and by other pollutants washing down from Enniscorthy and beyond. Net fishing for salmon had declined during my teenage years – it once seemed to be the after-work activity of every man in the parish, to bring in some extra cash in the 80s, but a decade later it had gone quiet. The salmon were no longer there, either due to the state of the water, or overfishing on the river, or out at sea.

I seem to have grown up with the subconscious knowledge that the river and the land mattered. That while things were never pristine, nor completely natural, now they were changing too fast, for the worse, during my own adolescence. As I’ve grown older, this has, in fits and starts, evolved into an understanding that we are living on a finite planet, with finite resources, and we are living like there’s no tomorrow. And they way we’re carrying on, tomorrow might just be fairly unpleasant; there will be no fish in the rivers, or the sea. Our farmland will be poisoned, and the air will be full of CO2 from our burning of oil, coal and gas. Predictions, as far as they go, suggest that Ireland will get wetter as the climate warms. More rain – can you believe that?

After the North Atlantic voyage, one incredible experience followed another. In early 2005, I spent two months working in Inari, Finnish Lapland, 300km north of the Arctic Circle as part of a partnership with Sami reindeer herders – the indigenous people of Norway, Finland, Sweden and part of Russia – to protect Europe’s last original northern forest from being turned into wood pulp for the paper industry. Camping in temperatures of -25C, being intimidated by heavies hired by the logging industry, it was one of the toughest campaigns I’d worked on, and but also one of the most revelatory, in terms of being introduced to new environments and cultures. In 2011, two years later, I returned to Inari to toast our success with Greenpeace folks based in Helsinki and local activists – finally, after years of campaigning and political wrangling, 40,000 hectares of original old growth boreal forest was protected – partly thanks to the initial push we made in 2005.

Several trips later, I was in Cape Town, to join the Esperanza, for a cruise up the west coast of Africa, working with Greenpeace, the government of Guinea, and the Environmental Justice Foundation, to track down the foreign fishing boats – Irish included that were stealing fish from the artisanal subsistence fisherman to go to sea in their small pirogue boats. We saw some alarming things along the way – rotting Chinese trawlers, left abandoned offshore with skeleton crews, men who hadn’t set foot on land or seen their families in perhaps two years. We pursued a Korean freighter hauling 11,000 boxes of stolen fish from Guinean waters 2,000 all the way to Las Palmas in the Canaries, where its owners tried to offload it as “Produce of the EU”. We blocked the offloading, and after a long wait over Easter 2006, the Spanish government seized the vessel, and returned all of the fish to Guinea.

By early 2007, I’d become part of the Greenpeace anti-whaling campaign, which took me all over the world – to meetings in Alaska and Chile, to Japan to campaign for justice for two Greenpeace colleagues who were prosecuted for standing up to the corruption behind Japan’s whaling operations. And of course, it took me to Antarctica, twice. I never set foot on the continent, but spent weeks travelling through the incredible icescapes of the Southern Ocean, far from what we call civilization. There’s very few other humans here – so we were more likely to encounter large animals like humpbacks; one morning we had 40 of them playing around the ship, launching their 30 tonne bodies into the air and crashing back down in the icy sea.

That campaign, one that environmental organised waged for decades finally found success in April 2014, when Japan announced the cancellation of its whaling expeditions, after the International Court of Justice found its claims of that it needed to hunt whales for scientific to be utter nonsense. Protecting whales in Antarctica might seem like a strange occupation for a lad from Crossabeg, but it’s not so long ago that the streetlights of our towns and cities were lit by whale oil. And Wexford’s Hook Head has become one of Europe’s foremost destinations to see migratory humpbacks and other species.

By 2009 and 2010, I was at the other end of the planet, sailing around the stunning coasts of Greenland and Spitsbergen, to places where in many cases people hadn’t been in decades, if at all. We worked with climatologists, glaciologists, oceanographers and marine biologists to measure the movement of Greenland’s massive glaciers, and how their melt rate could affect sea level rise. We investigated the thinning sea ice over the Arctic Ocean, which is retreating, year on year. And we looked at how ocean acidification, caused by CO2 pollution absorbed by the sea, could be wreaking havoc the shell-making process of sea creatures – and the knock on effect for the larger animals that rely on them, from fish and seals to whales and polar bears.

Voyages like this may seem a far cry from Crossabeg, but for me, it’s part of the same planet. Sea level rise will affect anyone near a coast. The front step of the thatched house that I lived in until I was eight years old is not much higher than the Slaney at high tide. With spring tides and floods, you can add a few centimetres. With more fresh water entering the oceans in the Arctic, we could see the estuaries rise by far more in the coming decades. Changing sea ice conditions in the Arctic could change how the Gulf Stream behaves as it sweeps up across Western Europe. Changes in our oceans will affect fish life everywhere including in the Slaney. Nothing happens in isolation.

It’s not all doom and gloom; we’re all waking up to the effects of humanity’s behaviour, and to some extent, we’re cleaning up our act. I recently spent an Easter Monday evening watching an otter foraging for fish from in front of the house. While I was there, an owl swooped past on its nightly raid. Crossabeg might not be the West of Ireland, or the Serengeti or Yellowstone, but it has its own wildness. We should cherish this, and make sure we never lose it.

Writer, photographer and environmental campaigner Dave Walsh is from down by the Slaney in Ballydicken. He is an advisor to a number of environmental organisations, including the Antarctic & Southern Ocean Coalition, the Pew Charitable Trusts, and Greenpeace.

and also: The River Flows

Pingback: The Slaney River and the World

Pingback: What my son taught me about the moon

Comments are closed.